News & Updates

-

Watch: Essential Lighting Tips All Filmmakers Should Know About

Posted by NALIP on July 22, 2016

Light is one of the single most important elements in filmmaking.

As a cinematographer, much of your job centers around shaping light. Not only do you have to know where to get it, but you also have to know where to put it. In the video below, Simon Cade of DSLRguide uses a real set to...ahem...illuminate 4 basic lighting considerations that professionals take into account every day when making these decisions:

The four key concepts we can take away from Cade's video are:

Use what's available

Available light is what most beginner/no budget filmmakers are used to. It's the lamp on your nightstand. It's the bulb in your living room. It's the sun. It's the moon. It's the streetlight on a busy city street. This kind of light can be really useful if you don't have access to a pro light kit, especially when used with light modifiers like scrims, umbrellas, or even a big ol' white sheet. However, available light has its limitations and downfalls, including various light temperatures, power/brightness, location, and, you know, the fact that you and your set are orbiting around it making it difficult to shoot with it for long periods of time. (We're looking at you, Sun.) Cade's other tips show how one might get around these limitations.

Make sure your lighting choices are motivated

If you do have access to professional lighting equipment, you can start to make more motivated lighting choices. You can choose your keys and fills to help make your scene look more cinematic, to enhance your storytelling, and to correct any issues you might have with the way your scene is being lit. But the important thing to remember is that these decisions shouldn't be arbitrary, they should be motivated. They should serve a purpose. They should make the images and/or the story better—preferably "and."

Learn how to hide your lights

This is actually a skill you really have to practice to get any good at, because anyone can hide a light so it doesn't show up on camera, but the real artistry comes from knowing how to do it and still get the results you were looking for. This actually takes a ton of creativity and inventiveness, but, again, with some practice you'll get a keen sense of the most unobtrusive and effective light placement.

Experiment

It's easy to get complacent and rely on tried and true methods for lighting a scene, but wherever you see an opportunity to experiment with lighting, take it. Play around with colors, placement, shadows, different types of bulbs, and modifiers. Use combinations you've never tried before. Try being more bold if you're subtle or more subtle if you're bold. Film and cinematography is an ever growing language that is eagerly waiting for new words to be added to it. As Cade says in the video, "It never hurts to ask yourself, 'Should we try something unpredictable?'"

-

The Black List Wants to Bring You to Sundance

Posted by NALIP on July 22, 2016

by Jon Fusco

You can bring your script along, too.

nofilmschool.com

nofilmschool.comProducer Cassian Elwes and The Black List founder Franklin Leonard started the Independent Screenwriting Fellowship four years ago to provide one lucky unrepresented screenwriter with an opportunity for an all expenses paid trip to the Sundance Film Festival. Now, they've made room for one more. That's right: what was formally one spot is now two.

The decision to expand the screenwriting fellowship was brought about this year when Elwes couldn’t decide between two writers, so he ended up bring both to Sundance.

Your script, once submitted, will be placed under consideration for a shortlist of ten screenplays. Those are then sent to Elwes, who will choose his companions personally. With films like Dallas Buyer's Club, The Butler, and I, Origins underneath his belt, we'd say that's a pretty decent Sundance date.

Eligibility for the fellowship requires that your lifetime writing earnings not exceed $5,000—which, for most of us, shouldn't be too hard to meet. The screenplay also must have "indie sensibilities."

Writers have until November 5 to submit a script. One key point to note, however, is that the script most be hosted and submitted through The Black List, which costs writers $25 for a submission and $75 for evaluation. If your script is already on the site, however, then there are no additional fees.

Sign up here.

Check this out on nofilmschool.com

-

The 3 Key Psychological Hooks to Creating Compelling Characters

Posted by NALIP on July 22, 2016

by Tim Long

nofilmschool.com

nofilmschool.comWhat does the writing behind film's most successful characters have in common?

While artificial intelligence has been busy identifying the most successful story arcs in film, I’ve been focused on the one thing that algorithms will never understand: human characters. In particular, I’ve found three ubiquitous yet distinguishing features that all compelling characters share in successful screenplays and films.

What makes these three characteristics so significant is the psychological effects that they have on an audience, as well as their functional effects on story. In short, all three characteristics contain a universal principle that resonates with us as individual characters ourselves.

1. Distinction

Distinction is whatever makes your character different and unique to the audience. Although it may seem that people gravitate toward the comfortable and familiar, I’d argue that we’re actually predisposed to the concept of distinction without being conscious of it. People by nature are organically drawn to anything that is new or different—sights, sounds, experiences, etc.

This psychology also plays out with respect to the characters in our screenplays. Distinction within a character is what piques our interest and causes us to want to know more about the person. It’s the unconscious prompt that draws us into their world. And it can come in many different forms. It can be a specific personality, a contradiction, a talent, an aspiration, an idiosyncrasy, a job, a character flaw, or an amalgam of several things.

Ryan Gosling in 'Drive'Ryan Gosling’s character in Drive is a terrific example of this at play. He’s a Hollywood stuntman who moonlights as a getaway driver. That unexpected twist is what made him totally distinctive to us as an audience. It’s what draws us to him right from the get-go and generates the requisite intrigue that aroused our interest in him as a unique individual.

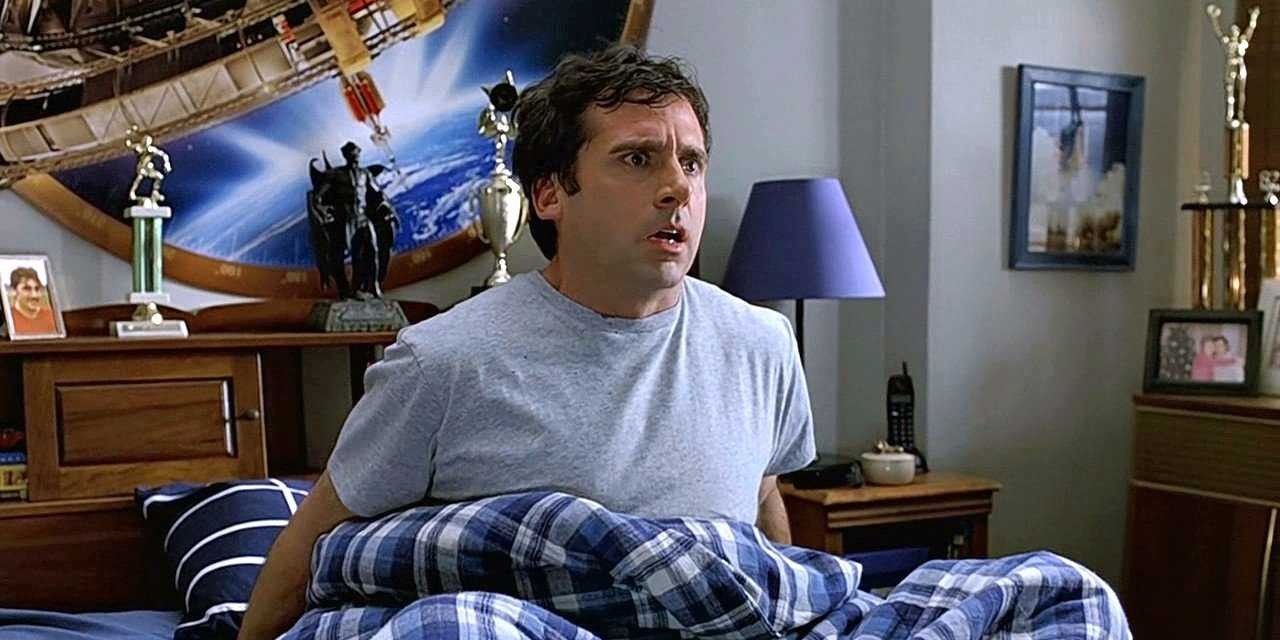

Ryan Gosling in 'Drive'Ryan Gosling’s character in Drive is a terrific example of this at play. He’s a Hollywood stuntman who moonlights as a getaway driver. That unexpected twist is what made him totally distinctive to us as an audience. It’s what draws us to him right from the get-go and generates the requisite intrigue that aroused our interest in him as a unique individual.Or take Steve Carell’s character in The 40-Year-Old Virgin. His distinction lies in the title itself. A normal, kindhearted man who hasn’t had a sexual encounter, not for some specific personal or religious reason, but because he just gave up trying, is curiosity Valhalla. It compels us to want to know more about him as a character.

Or think about Clint Eastwood’s character in the Academy Award-winning film, Unforgiven. He’s a former outlaw and killer who has been transformed by marriage. Being a repentant murderer trying to do right by his children by collecting a bounty, coupled with his violent past, is an aspiration and backstory that coalesced into a truly distinctive character. One that coaxed us into the story and caused us to want to know more about him.

2. Empathy

People connect with other people through empathy. Our innate ability to sense other people’s emotions, as well as to imagine what someone else might be feeling, is hardwired in us as a species. When we see a child crying tears of joy as they reunite with their returning military mom or dad, and we notice ourselves choking up, that’s empathy. When we see someone struggling with a problem and feel a need to help, that’s empathy.

Empathy is what moves us to share in another’s struggle, to really see the world through their eyes. It’s our capacity to identify with the feelings and concerns other people have. It allows us to look at others and feel that they are somewhat like…well, us.

Understanding this facet of intrinsic human nature is the key that unlocks your character’s relatability to an audience. How so? Because in order for the audience to connect with your character, they have to connect with something in themselves that knows what your character is feeling. Simply put, your character gives you the ability to create empathy, and empathy allows the audience to personally connect to your character and their story.

Steve Carell in 'The 40-Year-Old Virgin'Let’s go back to our example characters, starting with Ryan Gosling in Drive. His desire to help his neighbor out of a violent situation, despite the fact that he’s falling in love with the man’s wife, is something we can empathize with. That sacrifice and emotional duality is what causes us to relate to him as a human being and creates a personal connection with us as an audience.

Steve Carell in 'The 40-Year-Old Virgin'Let’s go back to our example characters, starting with Ryan Gosling in Drive. His desire to help his neighbor out of a violent situation, despite the fact that he’s falling in love with the man’s wife, is something we can empathize with. That sacrifice and emotional duality is what causes us to relate to him as a human being and creates a personal connection with us as an audience.After learning that Steve Carell’s character in The 40-Year-Old Virgin is, in fact, a virgin, his friends rekindle his desire to get back into the game again. However, he wants more than sex; he’s looking for companionship. And that’s a universal human need that we can all relate to. It’s what produces an empathetic connection in us as an audience.

Externally, Clint Eastwood’s character in Unforgiven desires to provide a better life for his motherless children by doing one last killing and collecting a bounty. This allows us to easily empathize with him. Internally, his fear of collecting a bounty by having to kill two cowboys, which in turn might cause him to revert back to being the man he used to be, generated an additional level of connective empathy. The power of empathy is evident in that we still empathized despite the fact that he was a known thief and murderer.

3. Impetus

A character’s impetus is defined as the “why” behind their desire; it’s the thing that is personally motivating them to attain that desire.

As mentioned above, Ryan Gosling’s desire was to help his neighbor out of a violent situation, despite the fact that he’s falling in love with the man’s wife. So what’s his impetus? What’s personally motivating him to want to attain that desire? What’s his “why”? The answer lies in a key scene where Gosling had dinner with the neighbor, the neighbor’s wife, and their young son. It’s here Gosling sees a hint of happiness in the man’s wife as her husband reminiscences on how they became a family. This is when we as an audience realize Gosling wants the man’s wife to be happy, but he recognizes that part of her happiness lies in wanting to keep her family together because her son loves his father. And that’s the personal motivation that causes us an audience to invest in Gosling’s character.

Steve Carell’s Virigin character wanted to get back into the game in hopes of finding companionship. So what’s his impetus? It’s rooted in the fact that he’s been alone for so long that he’s filled his world with inanimate man-child objects in order to make his life happy. Except he has no one to share his stuff with. His only friends are an old couple he watches Survivor with. The desire for more intimate companionship is the impetus that drove him to get back in the game. It’s what endeared us to him and made us invest in his story.

In Unforgiven, the desire of Clint Eastwood’s character was to provide a better life for his motherless children. His impetus is both simple and thoughtful enough for us to invest in. Like most parents, he wants his children to have a better life than he had—and a better life than they’re currently living, eking out a struggling existence on a tiny, failing, pig farm in the middle of nowhere.

Distinction, empathy, and impetus are the psychological cornerstones in crafting a compelling character with emotional resonance. So as you begin to develop your character, keep in mind: Distinction draws the audience in. Empathy makes the audience relate. And Impetus keeps the audience invested.

Check this out on nofilmschool.com

-

How To Do the Possibly Impossible: Break Into Commercial Directing

Posted by NALIP on July 22, 2016

by Liz Nord

nofilmschool.com

nofilmschool.comVeteran commercial producer and indie filmmaker Jen McGowan shares practical tips for breaking into the ad biz.

Professional commercial directors can make about $30K per shoot day, which—let’s face it—is no small chunk of change for your average indie filmmaker. In order to create the financial freedom to build feature film careers, many indie makers aspire to get involved in some aspect of commercial production.

Kelly & Cal director Jen McGowan has been behind the scenes on ad shoots for almost 20 years, during which she has shot in four countries, with everyone and everything from chimpanzees to the New York City Ballet to P. Diddy. However, though some bigger name directors like Wes Anderson and Michel Gondry have tried their hand at commercial directing, the industry is not easy to get a foothold in (especially for women, as Mashable reported). In fact, in her entire career, McGowan has worked with only three female directors and one director of color.

With the stakes high, but the odds stacked against newcomers, No Film School asked McGowan for her insider perspective on how the industry works—and how you can get a leg up.

NFS: What does it mean to be a commercial producer? What do you do?

McGowan: I work as a freelance producer and production manager. What that means is, I get paid on a day rate to hire everybody to show up, put everything together, hand it in to the production company, and walk away. That's it. In the commercial world, my role is just the creation of the shoot. We don't really deal with post. We don't deal with special effects. We don't deal with music. It's the production of the shoot.

NFS: How do the directors get hired?

McGowan: The brand hires the agency, the agency goes out to production companies with their boards, and the production companies present directors who are on their rosters. The agencies select directors to present to the brand, the brand chooses a director, the director gets hired. The director usually has a producer that they work with on a regular basis. Then, they execute the shoot.

NFS: How does someone get represented by a production company?

McGowan: You have to have a series of spots on a reel. The thing about the commercial world is it's super specific and literal. For example, I saw this post on one of the commercial listservs that belong to: "I need a director that has Rube Goldberg experience." You know those Rube Goldberg machines? That specific.

But there are areas to break in if you’re willing to be specific. For example, I'll tell you where there is an opportunity for directors to work: tabletop directing. Think close-ups of water pouring out of a bottle cutting to into a glass, an ECU of a set of a woman’s manicured nails. Highly art-directed food, toys, or other products Basically a bunch of close-up shots.

NFS: Wow, so it doesn't matter if the director has any sort of creative vision as long as they shoot the very specific thing that the company wants to sell?

McGowan: I am not kidding you. It’s just a different world than features. In the Rube Goldberg case, they wanted someone that had that on their reel so that they could do another thing exactly the same [way]. It's very frustrating for young directors. They're like, "I don't want to be put in a box." I'm like, "No, you don't understand. You need to put yourself in a box."

NFS: What do you mean by that?

McGowan: You want to be put in a box. If you don't decide to put yourself in a box, you're not going to work, because people aren't going to understand what the fuck you do. You need to say, "I do dog food commercials. That's what I do. I'm an expert in dog food commercials." Or, "I do car commercials." There are people who do exclusively car commercials for 40 years.

There are only a few guys in the world who do car commercials. And that is why it’s so hard to break in, because there are only a few guys who do it, period. And when those guys die, their assistants do it.

NFS: Can a reel contain spec commercials and still be effective?

McGowan: Absolutely. But if you are doing a spec with a known brand, you'd better be speaking the language of that brand.

Take Dove. It is a known brand. You understand the feeling of Dove. You understand what they're communicating. You don't do a Dove commercial and use punk rock music and cast all boys. You need to think properly for the brand. By the way, like all things in life, there are exceptions, but this is the general rule in this world.

It’s kind of like surfing: you want to be just in front of the wave, but if you're too far in front of the wave, you're going to get crushed. Nobody understands it if your idea is five years [too early]. They want you to only be half a year ahead.

NFS: But you do hear about indie directors making commercials, especially documentary people.

McGowan: Documentaries are slightly different because they are a genre in and of themselves, like cars are a genre. Music is a genre. Babies are a genre. Tabletop is a genre. You want to be able to brand yourself as precisely as possible, so the best thing somebody could do if they want to work in commercials is to create a reel of three to four commercials that speaks clearly to their brand, of what kind of commercial director they are. And it needs to be high-quality. This is something that filmmakers really don't understand. Unless they're doing comedy, they have to have high production values, particularly in commercials. And if they’re doing comedy, it better be funny.

Look critically at the quality of your work. I don't mean in terms of creativity. I would never judge anyone else's creativity. But in terms of quality, ask yourself, “Does this actually look like anything on television, or in a theater? Is this something better than to just show my friends and my family?” Because if it's not, don't show it to people!

NFS: Aside from just money, what are the pros of trying to break into commercial directing?

McGowan: Well, it is a shit ton of money, and that's legitimate. Also, you get to work with some of the top crews in the business. You get to work with some of the best tools and toys. You get to work in the best locations. You get to spend hours on a single shot. I would say the average budget of a 30-second commercial— and this is just the shooting budget, mind you, which doesn't include post or talent—is usually about $300,000.

NFS: So it's like a whole indie film micro-budget just for the camera department for one spot.

McGowan: Yeah, that's fun to work like that. It's great to work with a big crew, a professional crew that knows what the fuck they're doing. It's amazing.

It’s funny because I had an interview on the film side of things a couple months ago. An executive said to me, "Oh, you must be used to working with smaller crews." I thought, "What?" Why would he say that? I thought that was so weird. And then I realized, it was because he saw me as an indie filmmaker and doesn't know that I work in commercials, too, because I keep those worlds very separate. But I am much more comfortable on crews of 60 or 70 than I am on these little cut-down indie film crews. The smaller crews stress me out.

NFS: When thinking about what production companies to approach after you’ve made your reel, is the AdAge Production Company A-list a good place to start?

McGowan: Oh my god, yeah. Those are the top companies. But there are tons others too. Just do your research.

NFS: How would you go about getting your reel in front of them?

McGowan: You just need to reach out and cold call, but you need to test out your pitch and your reel on the companies you’re less interested in first. If you have your list of 10 people that you want to go to, put them in order of importance and work your way up. Because if you get three no's in a row, don't waste your A people. Start again.

One more thing: I would really urge people to understand that commercial directing is an industry. It is a career in and of itself. Sometimes what happens, especially with young filmmakers, is they say, "I'm going to do X to get to Z." In Los Angeles, where there is a monstrous industry, you need to do the thing you want to be doing. If you want to direct commercials, fabulous, direct commercials. But don't direct commercials because you want to be directing features. If you want to direct features, direct features. Done. Or you're going to do that for 20 years and realize, "Holy shit, my path was actually a complete diversion."

Check this out on nofilmschool.com

-

Hispanic Heritage Short Film Award Competition

Posted by NALIP on July 22, 2016

ShortsHD and the Hispanic Heritage Foundation will award the grand prize of $10,000 to a short film chosen in this year’s Hispanic Heritage Short Film Award competition.

The winning Hispanic filmmaker will receive a free trip to Washington, DC to screen the selected film at the Hispanic Heritage Awards held September 22, 2016, exposure to decision makers for broadcast deals, as well as additional award prizes such as participation with a round table of studio executives and experts to provide guidance to finalists.

The top five (5) finalists will be considered for a television broadcast deal on ShortsHD!

Get more information on hispanicshortsawards.com

Get the latest from NALIP news in your inbox. Sign up right here.

-

What Screenwriters Can Expect with Their First “General Meeting”

Posted by NALIP · July 22, 2016

by ScreenCraft

This Post originally appeared on the blog ScreenCraft. ScreenCraft is dedicated to helping screenwriters and filmmakers succeed through educational events, screenwriting competitions and the annual ScreenCraft Screenwriting Fellowship program, connecting screenwriters with agents, managers and Hollywood producers. Follow ScreenCraft on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

The “general meeting” is a term that is very abundant in Hollywood. It refers to the first meet-and-greet meeting that development executives and producers hold with screenwriters that have showcased talent through a spec script — a screenplay written independently by the screenwriter under speculation that it will be sold.

When novice screenwriters picture such meetings, they usually envision a long table with executives sitting around them, grilling them on their stories and characters. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Hollywood screenwriter Phil Hay (Crazy/Beautiful, Aeon Flux, Clash of the Titans, Ride Along, Ride Along 2) detailed the process of the general meeting — as well as what leads up to and follows it — through ScreenCraft’s very first podcast, which you can listen to in whole below.

We elaborate on his points to give screenwriters an idea of what those first meetings will be like, what they mean, and where they can lead.

The General Meeting is NOT a Pitch Meeting

“You show up. They have told you or your representative that they like your script, but they’re not buying it or can’t do anything with the spec, but they like you as a writer. They want you to come in. They want to meet you and just talk. And that’s not a meeting where you’re expected to be pitching something specific… it’s really to get a sense of who you are,” Phil explains.

Too many screenwriters go into these general meetings expecting to either re-pitch the script that got them in there, or to pitch a belly of other scripts or concepts they have.

That’s not what the general meeting is for. And if they wanted to pursue the script that got you this meeting, it would have already happened — or would at least be in the process of happening — through either an option or sale deal. Thus, you’re not expected to pitch the same script again. That screenplay has done what it needed to do for you. It got you into the room.

The general meeting, like Phil said, is all about them getting a sense of who you are as a person.

“They like your writing, otherwise you wouldn’t be there,” he points out.

Now it’s about building a relationship.

Building Relationships

“A big part of being a screenwriter is relationships… it’s the most important thing in terms of the business of screenwriting.”

That’s what the general meeting is really about — building relationships. There is truth to the old Hollywood adage It’s Who You Know, but not in the often misguided interpretation where you think you need to be related to Hollywood power players or have some sort of embedded relationship with them in order to break through. Not at all (although it does help). It’s about the relationships you build through general meetings, through networking, peer groups, etc.

Phil assures screenwriters by saying, “Sometimes people perceive that there’s this exclusive or exclusionary attitude. There are lots of things that are hard about this, but I don’t think that’s actually one of them… they are looking for you.”

And you must know that there are many ways to build relationships. Phil mentions how important it is to live in Los Angeles. There are exceptions, however, the reason living in Los Angeles can be so helpful is by being in the vicinity of those that can open doors for you.

It may be a neighbor that knows an entertainment lawyer.

“Entertainment Lawyers are an underrated group of people to send your stuff to,” he says.

It may be a co-worker at a regular day job that either knows somebody or has broken through themselves. Any number of relationships can make a difference. But the ones you make in these general meetings will be the true key to your eventual success.

Such relationships unlock doors into the Hollywood system.

The Atmosphere

“It’s usually really comfortable. It’s really fun. You’re not trying to sell them anything. You’re just being yourself.”

Screenwriters often picture a bunch of “suits” sitting across a long table in judgement when they imagine the general meeting. There is a context to that imagery, but not for these meetings.

Most are dressed in business casual — if that. You’ll sit in an office setting. You’ll be offered a bottle of water. It’s more of a conversation than an interview. You’ll talk about your background. You’ll likely discuss their company as well.

Overall, it’s very casual. You should feel relaxed, be yourself, and feel comforted that you’re not there to sell anything.

The best thing that you can do is to learn the habits and tricks that keep the conversation two-sided and comfortable — and it all starts by doing your homework.

Do Your Homework

“You should definitely be familiar with the kinds of movies that the people that work at that company have made and what they’re into,” Phil suggests.

This may be a simple and obvious point, but it’s so important because it will feed the conversation that you have with them. In this day and age, with IMDBPro and Wikipedia at your disposal — as well as the trades like Variety, Deadline, and The Hollywood Reporter — you should go into that meeting knowing every movie that they’ve made. You should know as much as you can about the individual(s) that you’re meeting with as well.

Find questions about those films that you may want to ask. Prepare some talking points centered around them. And even better, know some details about the people that you are meeting with and work them into the conversation. The more questions that you ask and the more talking points that you bring up will make it less of an awkward quasi-interview in their eyes and more of a casual, and hopefully memorable, conversation.

In short, don’t let the meeting be all about you. Let it be about them too. That’s how you build those true relationships that could carry over into your own screenwriting career.

“What Else Are You Working On?”

Once the small talk runs its course, you’ll be asked a variance of:

- “What else are you working on?”

- “What else have you written?”

This goes back to what you often read here about “stacking your deck” before you take anything out. If you have no other quality scripts, the meeting will likely be over before it ever started.

Beyond that, you need to know what you’re working on next.

“It’s important to have some idea of what you’re doing next, or what you want to do next. You absolutely don’t need to have some kind of pitch. And I would argue that you really shouldn’t unless they’ve asked for it,” Phil commented.

But he went on to say that when they do ask you what is next, you should have a general explanation that’s not a direct and pre-planned pitch.

“It’s to let those people know where your area of interest is.

So be prepared to casually answer those questions in a conversational manner, as opposed to a rehearsed pitch.

What Comes After the Meeting?

“Hopefully you’ve had a good experience and you walk out with them saying, ‘We would really love to see the script for ___ when you’re done with it.”

Phil goes on to say, “… if something sparks with them, they may have any number of things. They may have a book, they may have a magazine article, they may have an idea that one of the people that works there came up with that they’re looking for a writer for, etc.”

The “newness” that you have can be a benefit. They may be willing to take a chance on you if they like the writing enough. You won’t get the big bestseller that they’ve won during a rights auction, but they may have something smaller that they’re willing to let you take a shot at.

And sometimes nothing comes of it, at least not right away. Sometimes a meeting you had two years prior can lead to an assignment or sale two years later. That goes back to the relationships that you build.

And all too often it takes multiple meetings before anything happens.

Phil shared his own experience of the first general meetings that he and his writing partner had: “We had something like 40 meetings, at least, and the 41st meeting was someone we didn’t even send the script to. It was just someone who one of the other companies sent it to who really liked it… and they felt they had something for us and we came and met them and they gave us a shot.”

The first general meeting you have certainly won’t be your last. Even when things go well and you manage to secure an assignment, the Hollywood general meeting will be with you throughout your whole career.

The secret is to go in there, be yourself, and if it’s not a good fit, move onto the next.

Check this out on huffingtonpost.com

-

A New Disney Princesa Carries Responsibilities Beyond Her Kingdom

Posted by NALIP · July 16, 2016

“It was finally my time.”

Those words, spoken by the animated Princess Elena in the first episode of “Elena of Avalor,” a new Disney Channel series, are meant to reflect power: The zesty teenager has reclaimed her tropical kingdom from an evil sorceress. But the line has a deliberate double meaning. With Elena, Disney has created — at long last — its first Latina princess.

“It’s not a secret that the Hispanic and Latino communities have been waiting and hoping and looking forward to our introduction of a princess that reflected their culture,” said Nancy Kanter, the Disney executive overseeing the show, which will begin on July 22 with toy and theme park tie-ins. “We wanted to do it right.”

Did the company succeed? Or is Elena, like some of her royal counterparts, about to run afoul of the princess police?

Few matters in entertainment are as fraught as the Disney princesses, a dozen or so characters led by Cinderella and Snow White that mint money for the Walt Disney Company but also are cultural lightning rods. People who love the princesses (they’re pretty and live happily ever after!) and those who despise them (they promote negative female stereotypes and unrealistic body images!) square off endlessly. Academics study their adverse societal impact, even as women dress like them for their weddings.

Add race and ethnicity, as Disney is increasingly doing with its cartoon heroines, and this is a minefield, especially because animation by its nature deals in caricature. In 2009, when Disney introduced its first black princess, Tiana, every corner of her film, “The Princess and the Frog,” was dissected for slights.

Aware of the scrutiny that “Elena of Avalor” will receive, Disney has loaded each 22-minute episode with Latin folklore and cultural traditions. Avalor has Aztec-inspired architecture. Episodes will include original songs that reflect musical styles like mariachi, salsa and Chilean hip-hop. Elena’s black hair, gathered in a luxuriant pony tail, is accented with apricot mallow, a flower native to Southern California and Northern Mexico.

“We brought in a whole lot of consultants to advise on everything,” Ms. Kanter said. “We wanted to make sure that she didn’t have a doll-like appearance, and we really wanted to steer clear of romance. She has male friends, as teenage girls obviously do, but we did not want it tinged with, ‘Ooh, they’re falling in love.’”

The first episode, made available through a Disney Channel app on July 1, has received positive feedback. “We were all very pleasantly surprised at how well the character was conceived,” said Axel Caballero, executive director of the National Association of Latino Independent Producers. “This is going to have a great impact.”

Already, though, “Elena of Avalor” has run into questions of princess parity, starting with the medium: Why is Disney introducing her through a television series aimed at children 2 to 11 and not in a full-fledged family movie, like her counterparts? “It really seems like a shun,” wrote Mandy Velez, a co-founder of Revelist, a publication targeted to millennial women.

For Rebecca C. Hains, author of “The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years,” the newest member of Disney’s royal court wins points for her heroism. In the first episode, Elena, after the deaths of her parents, tries to prove that she is ready to be queen, even though she is only 16.

“She’s not an ornament,” said Ms. Hains, an associate professor of advertising and media studies at Salem State University. “This is a princess with real political power, and that’s genuine progress.”

Still, Ms. Hains was cautious. “The mashing together of cultures gives me pause,” she said. Noting that older characters speak with Spanish accents and that Elena (voiced by the Dominican Republic-born Aimee Carrero) does not, Ms. Hains added, “Being modern and cool seems to mean talking like an American.”

Craig Gerber, who created “Elena of Avalor,” said the accents simply reflect a generational gap, a dynamic seen in many Latino families. He called the attention given to the Disney princesses “incredibly daunting,” but something that made the show better. “I really hope that young Latino children are happy to finally feel represented,” he said.

Serious people closely scrutinizing a cartoon character is the blessing and the curse of being Disney. Because its programming commands such attention, especially among children, the company is often held to a higher standard than competitors. Seemingly everyone has an opinion — often delivered as a demand — about what Disney should be doing with its characters, especially when it comes to diversity.

Elsa in “Frozen.” Credit Disney

In 2014, tens of thousands of people signed a petition pushing for a Disney princess with Down syndrome. In the spring, the company faced an online campaign to make Elsa from “Frozen” a lesbian. In recent weeks, an online brush fire has broken out around “Moana,” an animated Polynesian adventure to be released in November; an overweight male character has been criticized as offensive to Pacific Islanders.

“Elena of Avalor” comes as Disney tinkers with its princess strategy. The company has started depicting its princesses in more active poses on toy packaging and emphasizing their various personalities. Pocahontas and Mulan, for instance, are now more prominent.

(For the record, Princess Leia doesn’t count as a member of this group, at least in Disney’s eyes. And celebration over the introduction of a Pacific Islander princess in “Moana” has apparently been premature. Because the film barely mentions her lineage, the company will not be calling Moana a princess, according to a Disney spokesman.)

As for Elena, Disney contended that television was better than film. Rather than relying on parents to take their children to a theater, Disney will pipe “Elena of Avalor” directly into hundreds of millions of homes. The series, which already has a five-season “content plan,” will run in 163 countries and be translated into 34 languages. Disney has also tried to make the series look and sound more like a movie than a television cartoon.

“The goal is certainly to give it as cinematic a feel as possible,” said Tony Morales, who scored the series, drawing inspiration from José Pablo Moncayo, a Mexican musician.

Disney is certainly not skimping on Elena’s promotion, including in the toy aisles, where analysts say there is an opportunity to steal market share from Dora the Explorer, the Latina preschool character that Nickelodeon introduced 16 years ago. It typically takes up to 18 months after a show’s debut for related products to arrive in stores, but Elena items — stuffed animals, shoes, children’s bedding, backpacks, clothes — were made widely available on July 1. Books and Halloween costumes are still to come.

In other words, Disney’s expectations for a hit are high.

“We know that the Latino community is extremely vocal and active,” Ms. Kanter said. “As long as we tell a good story and create a character who is compelling and interesting and stands for something, I think the audience will be really pleased.”

Check this out on nytimes.com